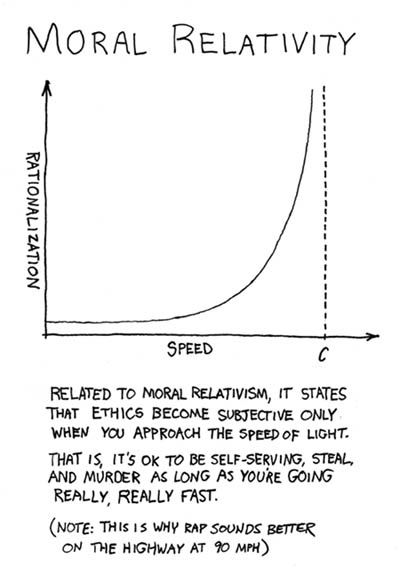

One of the things people like to ask about physics is, "What is the meaning of it all?" What does physics tell us about metaphysics--the ultimate reality behind all that is? Does Special Relativity support Moral Relativism? Does Quantum Mechanics provide a mechanism for consciousness or miracles? Does the Big Bang Theory prove God? No, no, and no.

In general, I feel the answer is that, no, physics does not tell us much about metaphysics. Furthermore, people who try to connect physics and metaphysics are often engaged in gross abuse of the science. Much more often, physics only helps us realize how much we don't know about metaphysics.

I've already tried to explain Special Relativity (Explained: 1, 2, 3), so I'm going to use it as an example to demonstrate my point.

First off, Relativity is not even related to Moral Relativism, or indeed any sort of subjectivist philosophy. They have nothing to do with each other. Yes, Relativity suggests that different observers can have different perceptions of time and space. But "observer" is a technical term that ultimately has no connection to humans, much less human ethical theory. Similarly, the details of time and space have little to do with ethics. If I say that time and space depend on your frame of reference, "frame of reference" is a technical term that depends on your velocity, not your point of view. People seem to think that Relativity tells us, "It all depends on your point of view," but the more accurate statement is, "It all depends on your direction and magnitude of motion." I guess that just doesn't have the same ring to it.

Another problem with the idea is that Special Relativity doesn't say everything is relative. Previous to Special Relativity, we used what we retrospectively call Galilean Relativity. In Galilean Relativity, the distance between two objects, and the time between two events would always remain the same, no matter your frame of reference. Time (Δt) and distance (Δx) are what we call "invariants". In Special Relativity, there is an invariant that combines space and time: what we call the "interval".* That means that though space and time are relative, space-time, taken as a whole, is not. Changing reference frames is analogous to rotating a keyboard (only you're actually rotating space-time). You may have changed the positions of the keys, but the shape of the keyboard stays the same. You may have changed space and time, but some things about space-time never change. For example, the speed of light always remains the same.

What Relativity does tell us is that our intuition of time and space can be incorrect. Our common experiences bias us towards thinking that time is absolute and independent of space, but that's not necessarily the case. Therefore, if you want to philosophize, you should be careful about your assumptions about time and space. If you want to talk about the cause of the universe, you should be careful with ideas like "before" and "after", since these concepts may or may not exist independently of the universe. Furthermore, in these matters, I think it is irrelevant whether Relativity is in fact true. Relativity is just a heads-up to philosophers to be careful with hidden assumptions. Ideally, philosophers would realize this without science's help, but whatever it takes.

*For the record, the equation for the interval is (ΔS)2 = (Δx)2 - (cΔt)2

Saturday, January 19, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

5 comments:

"For the record, the equation for the interval is (ΔS)2 = (Δx)2 - (cΔt)2"

How about some more explanation of that statement? How is the equation derived?

Good question.

First, consider classical physics without Relativity, and in one dimension. Every event has a set of coordinates (x,t) that specifies the location and moment in time. But these coordinates change to new ones (x',t') depending on your velocity. The equations governing the change in coordinates is called the Galilean transformation.

x' = x - vt

t' = t

In these equations, t' is always the same as t, meaning time never changes. No matter how fast you go, the event will be just as far in the future.

Under Special Relativity, we do not use the Galilean transformation, but instead use the Lorentzian transformation.

x' = ɣ(x-vt)

t' = ɣ(t - vx/c^2)

ɣ = 1/sqrt(1-(v/c)^2)

Obviously, these equations are a bit more complicated, but it's still just a matter of math to show that (x')^2-(ct')^2 equals (x)^2-(ct)^2.

It's difficult translate the interval into any sort of intuitive concept like you could with Δt. All it means is that if you calculate this particular value for an event, then you will always get the same value. On a space-time diagram, the event will always fall on a particular hyperbolic curve.

If you calculate the interval between two points on a photon's path, then you will always get an interval of zero. So no matter your reference frame, the interval between the two points will remain zero, and the speed of light will remain the same.

I should probably clarify a few more things.

(ΔS)^2 is the interval. You can either call it the "interval" or you call it "delta S squared".

The interval has very little physical meaning to it. The interval is just this particular value that you get when you do a lot of math.

You do not need to actually understand the equations I wrote above (unless you're studying physics). They only serve to demonstrate the basic idea of how to prove that the interval is constant.

Anyways, if I am unclear (and I know I'm unclear) then please ask specific questions. If the questions are too general, I'll probably end up blabbering on and on about the entire theory of Relativity.

The interval is invariant under Galilean transformation too.

Spacetime is conserved because space and time is conserved.

It's simple.

Actually, the interval is not conserved in Galilean relativity, though you might have been led to believe so by the way I've explained it. I sort of lied about Δx being an invariant in Galilean relativity. It isn't actually invariant unless we consider the distance between simultaneous events.

Long story short, it's not so simple after all, as much as we'd like it to be.

Post a Comment